Pompeii is a partially buried

Roman town-city near modern

Naples in the Italian region of

Campania, in the territory of the

comune of

Pompei. Along with

Herculaneum, its sister city, Pompeii was destroyed and completely buried during a long catastrophic eruption of the

volcano Mount Vesuvius spanning two days in 79 AD. The eruption buried Pompeii under 4 to 6 meters of

ash and

pumice, and it was lost for over 1,500 years before its accidental rediscovery in 1599. Since then, its excavation has provided an extraordinarily detailed insight into the life of a city at the height of the

Roman Empire. Today, this

UNESCO World Heritage Site is one of the most popular tourist attractions of Italy, with approximately 2,500,000 visitors every year.

[1]History

Early history

The archaeological digs at the site extend to the street level of the 79 AD volcanic event; deeper digs in older parts of Pompeii and core samples of nearby drillings have exposed layers of jumbled

sediment that suggest that the city had suffered from the volcano and other seismic events before then. Three sheets of sediment have been found on top of the lava that lies below the city and, mixed in with the sediment, archaeologists have found bits of animal bone,

pottery shards and plants. Using

carbon dating, the oldest layer has been dated to the 8th-6th centuries BC, about the time that the city was founded. The other two layers are separated from the other layers by well-developed soil layers or Roman pavement and were laid in the 4th century BC and 2nd century BC. It is theorized that the layers of jumbled sediment were created by large

landslides, perhaps triggered by extended rainfall.

[2]The town was founded around the 7th-6th century BC by the

Osci or Oscans, a people of central Italy, on what was an important crossroad between

Cumae,

Nola and

Stabiae. It had already been used as a safe port by Greek and

Phoenician sailors. According to

Strabo, Pompeii was also captured by the

Etruscans, and in fact recent excavations have shown the presence of Etruscan inscriptions and a 6th century BC

necropolis. Pompeii was captured for the first time by the Greek colony of

Cumae, allied with

Syracuse, between 525 and 474 BC.

In the 5th century BC, the

Samnites conquered it (and all the other towns of

Campania); the new rulers imposed their architecture and enlarged the town. After the

Samnite Wars (4th century BC), Pompeii was forced to accept the status of

socium of Rome, maintaining, however, linguistic and administrative autonomy. In the 4th century BC, it was fortified. Pompeii remained faithful to Rome during the

Second Punic War.

Pompeii took part in the war that the towns of Campania initiated against Rome, but in 89 BC it was besieged by

Sulla. Although the troops of the

Social League, headed by

Lucius Cluentius, helped in resisting the Romans, in 80 BC Pompeii was forced to surrender after the conquest of Nola, culminating in many of Sulla's veterans being given land and property, while many of those who went against Rome were ousted from their homes. It became a Roman colony with the name of

Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum. The town became an important passage for goods that arrived by sea and had to be sent toward Rome or

Southern Italy along the nearby

Appian Way.

Agriculture, water and

wine production were also important.

It was fed with water by a spur from

Aqua Augusta (Naples) built circa 20 BC by

Agrippa; the main line supplied several other large towns, and finally the naval base at

Misenum. The

castellum in Pompeii is well preserved, and includes many interesting details of the distribution network and its controls.

First century AD

A Map of Pompeii, featuring the main roads, the Cardo Maximus is in Red and the Decumani Maximi are in green and dark blue. The southwest corner features the main forum and is the oldest part of the town.

The main Forum in Pompeii

The Forum with Vesuvius in the distance

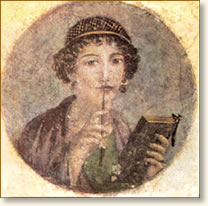

A married couple, identity disputed[3] Portrait on the wall of a Pompeii house. The excavated town offers a snapshot of Roman life in the first century, frozen at the moment it was buried on 24 August AD 79.

[4] The forum, the baths, many houses, and some out-of-town villas like the

Villa of the Mysteries remain surprisingly well preserved.

Pompeii was a lively place, and evidence abounds of literally the smallest details of everyday life. For example, on the floor of one of the houses (Sirico's), a famous inscription

Salve, lucru (Welcome, money), perhaps humorously intended, shows us a trading company owned by two partners, Sirico and Nummianus (but this could be a nickname, since

nummus means coin, money). In other houses, details abound concerning professions and categories, such as for the "laundry" workers (

Fullones). Wine jars have been found bearing what is apparently the world's earliest known marketing pun (technically a

blend),

Vesuvinum (combining

Vesuvius and the Latin for wine, vinum).

Graffiti carved on the walls shows us real street

Latin (

Vulgar Latin, a different dialect from the literary or classical Latin). In 89 BC, after the final occupation of the city by Roman General

Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Pompeii was finally annexed to the

Roman Republic. During this period, Pompeii underwent a vast process of infrastructural development, most of which was built during the Augustan period. Worth noting are an

amphitheatre, a

palaestra with a central

natatorium or swimming pool, and an

aqueduct that provided water for more than 25 street fountains, at least four public baths, and a large number of private houses (

domi) and businesses. The amphitheatre has been cited by modern scholars as a model of sophisticated design, particularly in the area of crowd control.

[5] The aqueduct branched out through three main pipes from the

Castellum Aquae, where the waters were collected before being distributed to the city; although it did much more than distribute the waters, it did so with the prerequisite that in the case of extreme

drought, the water supply would first fail to reach the public baths (the least vital service), then private houses and businesses, and when there would be no water flow at all, the system would fail to supply the public fountains (the most vital service) in the streets of Pompeii. The pools in Pompeii were used mostly for decoration.

The large number of well-preserved

frescoes throw a great light on everyday life and have been a major advance in

art history of the ancient world, with the innovation of the

Pompeian Styles (First/Second/Third Style). Some aspects of the culture were distinctly

erotic, including phallic worship. A large collection of erotic votive objects and frescoes were found at Pompeii. Many were removed and kept until recently in

a secret collection at the University of Naples.

At the time of the eruption, the town could have had some 20,000 inhabitants, and was located in an area in which Romans had their holiday villas. Prof. William Abbott explains, "At the time of the eruption, Pompeii had reached its high point in society as many Romans frequently visited Pompeii on vacations." It is the only ancient town of which the whole topographic structure is known precisely as it was, with no later modifications or additions. It was not distributed on a regular plan as we are used to seeing in Roman towns, due to the difficult terrain. But its streets are straight and laid out in a grid, in the purest Roman tradition; they are laid with polygonal stones, and have houses and shops on both sides of the street. It followed its

decumanus and its

cardo, centered on the forum.

Besides the forum, many other services were found: the

Macellum (great food market), the

Pistrinum (mill), the

Thermopolium (sort of bar that served cold and hot beverages), and

cauponae (small restaurants). An amphitheatre and two theatres have been found, along with a palaestra or

gymnasium. A hotel (of 1,000 square metres) was found a short distance from the town; it is now nicknamed the "Grand Hotel Murecine".

In 2002, another important discovery at the mouth of the

Sarno River revealed that the port also was populated and that people lived in

palafittes, within a system of channels that suggested a likeness to

Venice to some scientists. These studies are just beginning to produce results.

AD 62-79

The inhabitants of Pompeii, as those of the area today, have long been used to minor quaking (indeed, the writer

Pliny the Younger wrote that earth tremors "were not particularly alarming because they are frequent in Campania"), but on 5 February 62,

[6] there was a severe

temblor which did considerable damage around the bay and particularly to Pompeii. The earthquake, which took place on the afternoon of the 5th of February, is believed to have registered over 7.5 on the

Richter scale. On that day in Pompeii there were to be two sacrifices, as it was the anniversary of Augustus being named "Father of the Nation" and also a feast day to honour the guardian spirits of the city. Chaos followed the earthquake. Fires, caused by oil lamps that had fallen during the quake, added to the panic. Nearby cities of Herculaneum and Nuceria were also affected. Temples, houses, bridges, and roads were destroyed. It is believed that almost all buildings in the city of Pompeii were affected. In the days after the earthquake,

anarchy ruled the city, where theft and starvation plagued the survivors. In the time between 62 and the eruption in 79, some rebuilding was done, but some of the damage had still not been repaired at the time of the eruption.

[7] It is unknown how many people left the city after the earthquake, but a considerable number did indeed leave the devastation behind and move to other cities within the Roman Empire. Those willing to rebuild and take their chances in their beloved city moved back and began the long process of reviving the city.

An important field of current research concerns structures that were being restored at the time of the eruption (presumably damaged during the earthquake of 62). Some of the older, damaged, paintings could have been covered with newer ones, and modern instruments are being used to catch a glimpse of the long hidden frescoes. The probable reason why these structures were still being repaired around seventeen years after the earthquake was the increasing frequency of smaller quakes that led up to the eruption.

Vesuvius eruption

Main article:

Mount VesuviusBy the 1st century, Pompeii was one of a number of towns located around the base of the volcano, Mount Vesuvius. The area had a substantial population which grew prosperous from the region's renowned agricultural fertility. Many of Pompeii's neighboring communities, most famously Herculaneum, also suffered damage or destruction during the 79 eruption. By coincidence it was the day after

Vulcanalia, the festival of the Roman god of fire.

[8][9][10][11][12][13]

Pompeii and other cities affected by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The black cloud represents the general distribution of ash and cinder. Modern coast lines are shown.

A recent multidisciplinary volcanological and bio-anthropological study of the eruption products and victims, merged with numerical simulations and experiments indicate that at Vesuvius and surrounding towns heat was the main cause of death of people, previously supposed to have died by ash suffocation. The results of this study show that exposure to at least 250 °C hot surges at a distance of 10 kilometres from the vent was sufficient to cause instant death, even if people were sheltered within buildings.

[14]The people and buildings of Pompeii were covered in up to twelve different layers of soil which was 25 meters deep.

Pliny the Younger provides a first-hand account of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius from his position across the

Bay of Naples at

Misenum, in a version which was written 25 years after the event. The experience must have been etched on his memory given the trauma of the occasion, and the loss of his uncle,

Pliny the Elder, with whom he had a close relationship. His uncle died while attempting to rescue stranded victims. As Admiral of the fleet, he had ordered the ships of the Imperial Navy stationed at Misenum to cross the bay to assist evacuation attempts. Volcanologists have recognised the importance of Pliny the Younger's account of the eruption by calling similar events "

Plinian".

The eruption was documented by contemporary historians and is generally accepted as having started on 24 August 79, relying on one version of the text of Pliny's letter. However the archeological excavations of Pompeii suggest that the city was buried about two months later;

[15] this is supported by another version of the letter

[16] which gives the date of the eruption as November 23.

[17] People buried in the ash appear to be wearing warmer clothing than the light summer clothes that would be expected in August. The fresh fruit and vegetables in the shops are typical of October, and conversely the summer fruit that would have been typical of August was already being sold in dried, or conserved form. Wine fermenting jars had been sealed over, and this would have happened around the end of October. The coins found in the purse of a woman buried in the ash include one which includes a fifteenth imperatorial acclamation among the emperor's titles. This cannot have been minted before the second week of September. So far there is no definitive theory as to why there should be such an apparent discrepancy.

[18]Rediscovery

"Garden of the Fugitives". Plaster casts of victims still in situ; many casts are in the Archaeological Museum of Naples.

After thick layers of ash covered the two towns, they were abandoned and eventually their names and locations were forgotten. The first time any part of them was unearthed was in 1599, when the digging of an underground channel to divert the river Sarno ran into ancient walls covered with paintings and inscriptions. The architect

Domenico Fontana was called in and he unearthed a few more frescoes but then covered them over again, and nothing more came of the discovery. A wall inscription had mentioned a

decurio Pompeii ("the town councillor of Pompeii") but the vital fact that this indicated the name of an ancient Roman city hitherto unknown was missed.

[19] Fontana's act of covering over the paintings has been seen both as censorship - in view of the frequent sexual content of such paintings - and as a broad-minded act of preservation for later times as he would have known that paintings of the hedonistic kind which was later found in some Pompeian villas were not considered in good taste in the fiercely moralistic and classicist climate of the

counter-reformation.

[20]Herculaneum was properly rediscovered in 1738 by workmen digging for the foundations of a summer palace for the King of Naples,

Charles of Bourbon. Pompeii was rediscovered as the result of intentional excavations in 1748 by the Spanish military engineer

Rocque Joaquin de Alcubierre.

[21] These towns have since been excavated to reveal many intact buildings and wall paintings.

Charles of Bourbon took great interest in the findings even after becoming king of Spain because the display of antiquities reinforced the political and cultural power of Naples.

[22]Karl Weber directed the first real excavations;

[23] he was followed in 1764 by military engineer Franscisco la Vega. Franscisco la Vega was succeeded by his brother,

Pietro, in 1804.

[24] During the French occupation Pietro worked with Christophe Saliceti.

[25]

Cast of a dog that archaeologists believe was chained outside the House of Vesonius Primus, a Pompeiian fuller

took charge of the excavations in 1860. During early excavations of the site, occasional voids in the ash layer had been found that contained human remains. It was Fiorelli who realized these were spaces left by the decomposed bodies and so devised the technique of injecting

plaster into them to perfectly recreate the forms of Vesuvius's victims. What resulted were highly accurate and eerie forms of the doomed

Pompeiani who failed to escape, in their last moment of life, with the expression of terror often quite clearly visible (

[1],

[26][27] ). This technique is still in use today, with a clear

resin now used instead of plaster because it is more durable, and does not destroy the bones, allowing further analysis.

Some have theorized that Fontana found some of the famous erotic

frescoes and, due to the strict modesty prevalent during his time, reburied them in an attempt at archaeological censorship. This view is bolstered by reports of later excavators who felt that sites they were working on had already been visited and reburied. Even many recovered household items had a sexual theme. The ubiquity of such imagery and items indicates that the sexual

mores of the

ancient Roman culture of the time were much more liberal than most present-day cultures, although much of what might seem to us to be erotic imagery (e.g. over-sized phalluses) was in fact fertility-imagery. This

clash of cultures led to an unknown number of discoveries being hidden away again. A wall fresco which depicted

Priapus, the ancient god of sex and fertility, with his extremely enlarged

penis, was covered with plaster, even the older reproduction below was locked away "out of prudishness" and only opened on request and only rediscovered in 1998 due to rainfall.

[28]In 1819, when King

Francis I of Naples visited the Pompeii exhibition at the

National Museum with his wife and daughter, he was so embarrassed by the erotic artwork that he decided to have it locked away in a

secret cabinet, accessible only to "people of mature age and respected morals". Re-opened, closed, re-opened again and then closed again for nearly 100 years, it was briefly made accessible again at the end of the 1960s (the time of the

sexual revolution) and was finally re-opened for viewing in 2000. Minors are still only allowed entry to the once secret cabinet in the presence of a guardian or with written permission.

[29]Evidently due to its immorality, prior to or shortly after the destruction of Pompeii, one graffitist had scribbled "Sodom and Gomorrah" onto a wall near the cities central crossroads.

[30] Many Christians have since invoked the destruction of Pompeii in warning of divine judgment against rampant immorality.

[31][32][33]A large number of

artifacts from Pompeii are preserved in the

Naples National Archaeological Museum.

Geography

Pompeii, with Vesuvius towering above

The ruins of Pompeii are situated at coordinates

40°45′00″N 14°29′10″E / 40.75°N 14.48611°E / 40.75; 14.48611

40°45′00″N 14°29′10″E / 40.75°N 14.48611°E / 40.75; 14.48611, near the modern suburban town of

Pompei. (nowadays written with one "i") It stands on a spur formed by a lava flow to the north of the mouth of the

Sarno River (known in ancient times as the Sarnus). Today it is some distance inland, but in ancient times it would have been nearer to the coast. Pompeii is about 8 km (5 miles) away from Mount Vesuvius.

Tourism

The Circumvesuviana stop at Pompeii.

Pompeii has been a popular tourist destination for 250 years; it was on the

Grand Tour. In 2008, it was attracting almost 2.6 million visitors per year, making it one of the most popular tourist sites in Italy.

[34] It is part of a larger Vesuvius National Park and was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1997. To combat problems associated with tourism, the governing body for Pompeii, the Soprintendenza Archaeological di Pompei have begun issuing new tickets that allow for tourists to also visit cities such as Herculaneum and

Stabiae as well as the

Villa Poppaea, to encourage visitors to see these sites and reduce pressure on Pompeii.

Pompeii is also a driving force behind the economy of the nearby town of

Pompei. Many residents are employed in the tourism and hospitality business, serving as taxi or bus drivers, waiters or hotel operators. The ruins can be easily reached on foot from the

Circumvesuviana train stop called

Pompei Scavi, directly at the ancient site. There are also car parks nearby.

Excavations in the site have generally ceased due to the moratorium imposed by the superintendent of the site, Professor Pietro Giovanni Guzzo. Additionally, the site is generally less accessible to tourists, with less than a third of all buildings open in the 1960s being available for public viewing today. Nevertheless, the sections of the ancient city open to the public are extensive, and tourists can spend many days exploring the whole site.

In popular culture

Pompeii has been in pop culture significantly since rediscovery. Book I of the

Cambridge Latin Course teaches Latin while telling the story of a Pompeii resident,

Lucius Caecilius Iucundus, from the reign of Nero to that of Vespasian. The book ends when Mount Vesuvius erupts, where Caecilius and his household are killed. The books have a

cult following and students have been known to go to Pompeii just to track down Caecilius's house.

[35] Pompeii was the setting for the British comedy

television series Up Pompeii! and the movie of the series. Pompeii also featured in the second episode of the fourth season of revived BBC drama series

Doctor Who, named "

The Fires of Pompeii".

[36]In 1971, the rock band

Pink Floyd recorded the live concert film

Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii, performing six songs in the ancient Roman amphitheatre in the city. The audience consisted only of the film's production crew.

The song "Cities In Dust" by

Siouxsie and the Banshees is a reference to the destruction of Pompeii.

Issues of conservation

Fencing in the temple of Venus prevents vandalism of the site, as well as theft.

The objects buried beneath Pompeii were remarkably well-preserved for almost two thousand years. The lack of air and moisture allowed for the objects to remain underground with little to no deterioration, which meant that, once excavated, the site had a wealth of sources and evidence for analysis, giving remarkable detail into the lives of the Pompeiians. Unfortunately, once exposed, Pompeii has been subject to both natural and man-made forces which have rapidly increased their rate of deterioration.

Weathering, erosion, light exposure, water damage, poor methods of excavation and reconstruction, introduced plants and animals, tourism, vandalism and theft have all damaged the site in some way. Two-thirds of the city has been excavated, but the remnants of the city are rapidly deteriorating.

[37] The concern for conservation has continually troubled archaeologists. Today, funding is mostly directed into conservation of the site; however, due to the expanse of Pompeii and the scale of the problems, this is inadequate in halting the slow decay of the materials. An estimated US$335 million is needed for all necessary work on Pompeii.

Previous Post :

The Destruction of Pompeii, 79 AD

that began at about noon on August 24 of 79 AD. The main phases of the eruption lasted into the next day, and there may have been smaller scale activity in following days -- no historical record survives of the immediate aftermath of the explosive first 24 hours. The pumice fall deposits at Pompeii, 8 kilometers south of Vesuvius, were 2.5 to 3 meters deep. Much thicker pyroclastic flow deposits (up to 20 meters deep) overwhelmed Herculanum and other towns on the eastern slope. Tephra (bits of lava and other materials blown out in pyroclastic flows) was found 74 miles away, and finer ash flew for hundred of miles before settling out. The pillar of smoke and ash was visible from Rome, and some people there claimed they had heard the volcano's rumbling. Modern scientists estimate the volume of eruptive material at almost four cubic kilometers of magma. Contrary to earlier assessments, volcanologists today know that there were no lava flows in the 79 AD eruption. What came out was violently ejected from the top and sides of the volcano, mostly in the form of "inflated" pumice, that is, glassy fragments that had been expanded by volcanic gasses and steam. The measured volume of the inflated pumice is almost 9 cubic kilometers. Towns were flattened by devastating pyroclastic flows and by the weight of volcanic debris, the countryside was devastated, and thousands were killed, some of them still undiscovered today.

that began at about noon on August 24 of 79 AD. The main phases of the eruption lasted into the next day, and there may have been smaller scale activity in following days -- no historical record survives of the immediate aftermath of the explosive first 24 hours. The pumice fall deposits at Pompeii, 8 kilometers south of Vesuvius, were 2.5 to 3 meters deep. Much thicker pyroclastic flow deposits (up to 20 meters deep) overwhelmed Herculanum and other towns on the eastern slope. Tephra (bits of lava and other materials blown out in pyroclastic flows) was found 74 miles away, and finer ash flew for hundred of miles before settling out. The pillar of smoke and ash was visible from Rome, and some people there claimed they had heard the volcano's rumbling. Modern scientists estimate the volume of eruptive material at almost four cubic kilometers of magma. Contrary to earlier assessments, volcanologists today know that there were no lava flows in the 79 AD eruption. What came out was violently ejected from the top and sides of the volcano, mostly in the form of "inflated" pumice, that is, glassy fragments that had been expanded by volcanic gasses and steam. The measured volume of the inflated pumice is almost 9 cubic kilometers. Towns were flattened by devastating pyroclastic flows and by the weight of volcanic debris, the countryside was devastated, and thousands were killed, some of them still undiscovered today. had widened or perhaps because the volatility of the ejected material had decreased, the 33-kilometer-high ejecta plume collapsed on itself and poured down the slopes carrying with it newly released gasses and pyroclastics. Superheated surges, 500 degrees centigrade or more, rushed over and through the towns surrounding Vesuvius, killing everything -- humans, animals, vegetation -- in their path. The people of Pompeii, made visible in plaster casts centuries later, were not overcome by poisonous gasses as had long been conjectured, but rather they were killed instantly by thermal shock. In some areas, the heat surges were augmented by pyroclastic flows. Herculanum, long thought to have been inundated by post-eruption mud flows (lehars), was really buried by pyroclastic flows, the leading edge of which covered the 6 kilometer distance from the summit to Herculanum in just four minutes following the collapse of the ejecta plume. Almost all of the 4-5000 known deaths occurred during this phase, and almost all of the dead were found on top of the first phase pumice fall layer.

had widened or perhaps because the volatility of the ejected material had decreased, the 33-kilometer-high ejecta plume collapsed on itself and poured down the slopes carrying with it newly released gasses and pyroclastics. Superheated surges, 500 degrees centigrade or more, rushed over and through the towns surrounding Vesuvius, killing everything -- humans, animals, vegetation -- in their path. The people of Pompeii, made visible in plaster casts centuries later, were not overcome by poisonous gasses as had long been conjectured, but rather they were killed instantly by thermal shock. In some areas, the heat surges were augmented by pyroclastic flows. Herculanum, long thought to have been inundated by post-eruption mud flows (lehars), was really buried by pyroclastic flows, the leading edge of which covered the 6 kilometer distance from the summit to Herculanum in just four minutes following the collapse of the ejecta plume. Almost all of the 4-5000 known deaths occurred during this phase, and almost all of the dead were found on top of the first phase pumice fall layer.